- ABOUT US

- PROGRAM AREAS

- CONSERVATION APPROACH

- EDUCATION

- MULTIMEDIA

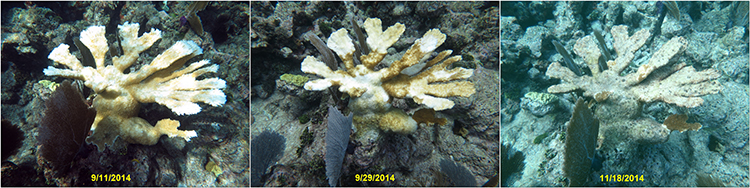

Scientists Document Impacts of Coral Bleaching on Florida's Elkhorn Coral

Summer 2014 brought higher water temperatures to the Florida Keys, triggering a bleaching event that damaged or killed a third of elkhorn corals (Acropora palmata) at seven NOAA monitoring sites in the Upper Keys.

Elkhorn corals were once one of the major reef-building coral species in the region, but are now listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. NOAA scientists have long-term monitoring data for several elkhorn coral sites in the region, and were able to document the impacts of the 2014 bleaching event as it progressed.

Bleaching, Disease and Some Signs of Recovery

Bleaching was first observed in late August and peaked in mid-September 2014.Coral bleaching takes place when corals are stressed by changes in conditions such as temperature, light or nutrients. They expel the symbiotic algae (called zooxanthellae) living in their tissues, causing them to turn white or pale. Without the algae, the coral loses its major source of food and may be more susceptible to disease.

Bleaching severity varied widely between elkhorn coral stands, among colonies within stands, and even at the individual colony level. As the conditions returned to normal, some of the more mildly bleached colonies recovered, regaining their symbiotic algae and their normal color.

However, those elkhorn corals that were more severely impacted remained bleached or began to die. At some sites, even corals that did not bleach or those that initially seemed to recover, succumbed to rapid tissue loss, suggesting a disease outbreak coinciding with the bleaching event.

Continued Monitoring

As November 2014 approached, the bleaching event was essentially over and few of the surviving colonies showed any signs of paling or bleaching. NOAA researchers will continue monitoring these sites to further document the extent and impact of this bleaching event and its aftermath.

Partners in this work: NOAA Southeast Fisheries Science Center Benthic Ecosystem Assessment and Research Unit and the NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program.

For more information, visit: http://www.sefsc.noaa.gov/.

About Us

The NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program was established in 2000 by the Coral Reef Conservation Act. Headquartered in Silver Spring, Maryland, the program is part of NOAA's Office for Coastal Management.

The Coral Reef Information System (CoRIS) is the program's information portal that provides access to NOAA coral reef data and products.

Work With US

U.S. Coral Reef Task Force

Funding Opportunities

Employment

Fellowship Program

Contracting Assistance

Graphic Identifier

Featured Stories Archive

Access the archive of featured stories here...

Feedback

Thank you for visiting NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program online. Please take our website satisfaction survey. We welcome your ideas, comments, and feedback. Questions? Email coralreef@noaa.gov.

Stay Connected

Contact Us

NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program

SSMC4, 10th Floor

1305 East West Highway

Silver Spring, MD 20910

coralreef@noaa.gov